I’ve been playing a lot of classic JRPGs lately. I’m currently in the middle of playthroughs of Dragon Warrior for the NES, Breath of Fire for the SNES, and Revelations: Persona for Playstation 1, and of course, my Final Fantasy IV Ultima livestream. All this JRPG playtime has got me thinking: JRPGs offer some cool lessons for better Dungeons and Dragons encounters.

JRPGs can teach us how to design more dynamic D&D encounters that don’t devolve into trading punches until somebody falls. But first, let’s look at the history of Dungeons and Dragons and JRPGs.

Dungeons and Dragons and JRPGs are Intrinsically Linked

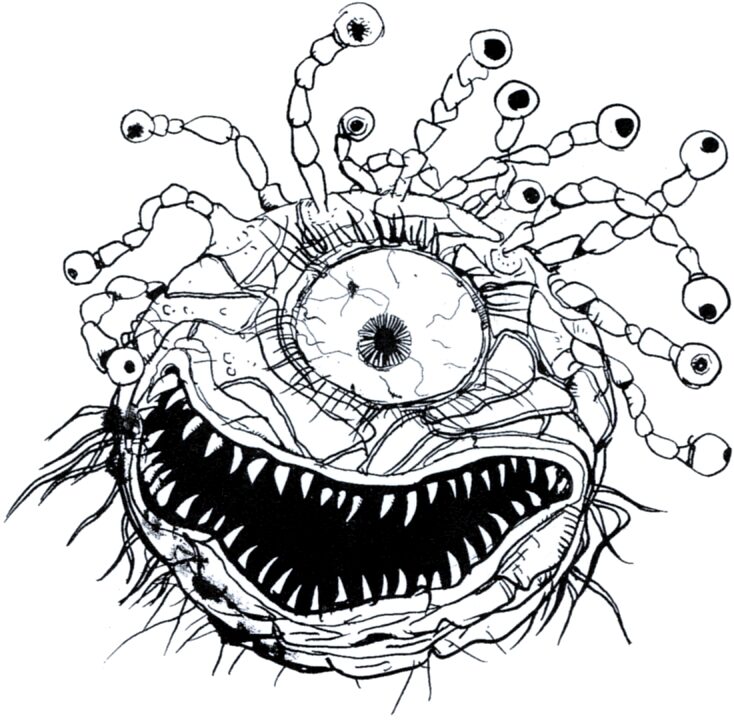

The two styles of games are more closely linked than you might think — the original Final Fantasy for the NES included some iconic monsters from Dungeons and Dragons (take a peek at the featured image of this article) — the original Japanese pixel art for the Eye monster looks almost exactly like a beholder, although the pixel art was changed for the US release. Creatures like mindflayers and sahaugin also make appearances.

That first Final Fantasy game also uses a slot-based magic system that tracks very close to the one in today’s 5th edition of Dungeons and Dragons, although later games would swap to a mana point system.

Under the hood, most JRPGs function very similarly to Dungeon and Dragons — you play a team of 3-5 characters, most of which are usually sorted into a class or archetype like fighter, mage, cleric, or thief. Throughout the game, different characters may join up or leave the group.

Party members gain experience points, and when they achieve a new level, their array of ability scores increase, they gain more hit points, and they unlock new spells and abilities.

Some games even offer some degree of multiclassing — the tactical JRPG Vandal Hearts for the Playstation has party members advance into new classes as they level, choosing to focus on different aspects like ranged damage or mobility, not unlike the old prestige classes from Dungeons and Dragons 3.5.

Artistically, the two styles of game have typically been separated by style — with character designs by Akira Toriyama (Chrono Trigger, Dragon Quest), Yoshitaka Amano and Tetsuya Nomura (Final Fantasy, Kingdom Hearts), and Tatsuya Yoshikawa (Breath of Fire), among many others, JRPGs have often drawn their graphical influences from Japanese styles of art like anime.

Dungeons and Dragons has traditionally skewed towards Western art styles — but this is starting to change, as we’re starting to see more and more Dungeons and Dragons players and even third party creators adopt more anime-inspired looks for their characters and NPCs.

JRPG Tricks For Better Dungeons and Dragons Encounter Design

Boss encounters in JRPGs often face many of the same problems as they do in Dungeons and Dragons — the action economy favors the players. A party of 3-5 characters will act much more often than a single boss creature, and this can lead to characters dogpiling the boss before they can be a real threat.

JRPGs offer some hints at how to solve these problems and create better boss encounters for Dungeons and Dragons.

Combat phases can improve your Dungeons and Dragons encounters

In many JRPG boss fights, bosses gain new abilities like a powerful defensive spell, summoning allies, or increasing their attack power once their hit points fall below certain thresholds. These are often accompanied by visual or audio clues — background music changes tempo or melody, the boss’s sprite changes, or the boss speaks to the player with some narrative exposition.

We’ve actually seen something like this in Dungeons and Dragons before — 4th edition had the bloodied condition, which triggered when a creature fell below half its maximum hit points. For many creatures, this triggered new abilities. Although 5th edition has largely stopped using the bloodied condition, there’s no reason you can’t implement it for a key boss fight.

Some JRPG boss fights take a different approach to phase shifts — Lost Number from Final Fantasy 7 and Magic Master from Final Fantasy 6 both go through phase shifts independent from their current hit point total, instead shifting phases in reaction to party actions.

Resistances, weaknesses, and counters can make a dull Dungeons and Dragons encounter interesting

In Final Fantasy 4, during the fight against Cagnazzo, the boss conjures a shield of water around himself. If struck with a physical attack while the shield is up, he takes minimal damage from it and immediately counters with Tsunami, a powerful wave of water that deals damage to your entire party. If you strike him with a lightning spell, however, the shield drops, making him vulnerable to the heavy physical damage your fighters can deal.

In Dungeons and Dragons, giving a boss creature a powerful reaction ability can really change up the way players must navigate a fight. Perhaps the boss’s reaction triggers when hit with a spell attack, forcing them to rely on physical attacks from melee warriors and summoned creatures. Maybe they use a reaction to summon an ally when a party member uses a healing spell near them.

D&D also has a system for handling damage resistance and weakness, but for most creatures, these elements are set in stone in the creature’s statblock. You can make the encounter more dynamic by giving the creature a spell or magic item to allow it to alter in resistances and weaknesses mid-combat.

Minions help deal with action economy

Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy 4 both have great boss fights that pits the party against a large primary boss, plus two smaller minions, one of whom takes a defensive or healing role, and another who takes a strong offensive role. In both games, the boss encounter doesn’t end until the primary boss is defeated, but doing so while the minions — who are stronger than the average monster — are still alive makes the fight much harder.

Adding minions can use up party resources and mitigate the action economy imbalance somewhat. Maybe the demon lord is accompanied by a powerful cleric for healing and defensive buffs and a rogue for strong single target damage, or maybe the goblin king summons lots of weak minions during the fight to overwhelm the party’s numbers.

In some JRPGs, killing all the minions is actually a trap — in one fight in Final Fantasy 4, if the boss’s minions are destroyed, it starts attacking the party with an extremely powerful attack it doesn’t normally use.

Like JRPGs?

Find out why the Final Fantasy IV Ultima romhack is my new favorite version of the game.

Buffs and debuffs can help a single boss survive against large parties

The Mikba fight in Breath of Fire 3 is a dynamic boss encounter that makes great use of buff and debuff spells and effects. Mikba can attack the party with a venom breath attack which deals the poisoned condition, has a high chance of immediately countering physical attacks, and can buff himself with the Resist spell to make himself invulnerable for a turn — to make matters worse, it’s a fight in which one of your party members has a chance to go berzerk, dealing heavy damage but potentially attacking your own party members.

Many similar effects appear in Dungeons and Dragons — boss creatures may have access to spells or abilities that can cause conditions like blinded, poisoned, frightened, exhaustion, and many more.

These conditions can hinder party members, forcing the party to make strategic choices: do they spend time to use spells or magic items to protect against or remove the conditions from their stricken allies? Or do they try to ignore the conditions and defeat the boss before they become too incapacitating for the party?

A countdown can really make for a suspenseful fight

In Final Fantasy IV, the fight against Bahamut is a race against time. The party really only has about five rounds to do as much damage as possible before Bahamut fires off Megaflare, a powerful AoE attack that can destroy the entire party.

In D&D, you can spice up an encounter by implementing a countdown too. Perhaps a powerful wizard is conducting a ritual a powerful eldritch horror — a magical shield protects him, powered by four arcane crystals. The party must destroy the crystals to drop the shield before the wizard completes the ritual in a few rounds.

I would avoid countdowns that lead to certain death, however. In JRPGs, if you fail a boss fight, you can simply load up your last save and try again. In order to maintain campaign continuity, that simply doesn’t work in Dungeons and Dragons campaigns, and no one likes a TPK.

Your D&D players will love recurring villains

JRPGs have great examples of recurring villains. Breath of Fire 3 has Balio and Sunder, a pair of roided-out gymbro unicorn-men assholes who pester your party throughout the early part of the game.

Final Fantasy has several great examples, like Ultros, a sleezy purple octopus who shows up in Final Fantasy 6, and Gilgamesh, an interdimensional swordsman who shows up in Final Fantasy V and several other games.

While many JRPGs tend to use these recurring characters for comic relief, you can use them in a variety of ways in Dungeons and Dragons. Maybe the party develops a rivalry with a a corrupt guard captain, who lets his underlings fight the party and escapes before they can face him.

It can be a little trickier to pull off a recurring villain in D&D, though. There’s always the chance that a party will kill the villain before they can escape — maybe they surprise you with a strategy you didn’t expect, or a series of lucky rolls quickly drops the villain faster than expected. iIf this happens, don’t force the issue. No one likes having a major triumph stolen from them just because the DM wants to bring the villain back later.

If this happens, you have a few options:

- Simply let the villain go. This is probably the best option. You can always adapt your plans and there’s always a new villain to fight. After all, if the party didn’t know the villain was intended to be a recurring character, you can introduce some other NPC to serve that role.

- Riff on the villain. Maybe the slain villain has a family member or a colleague who seeks out the party for revenge. You can make the new encounter thematically similar to the original, but make you introduce unique character traits and encounter elements so it doesn’t feel like you’re just cloning the first villain.

- Bring the villain back in a new form — maybe a necromancer revives the villain as an undead minion, or a mortal villain returns transformed into a demon or devil after their soul entered the afterlife. This can be a lot of fun, but don’t overuse it.

Dungeons and Dragons bosses need more hit points

Finally, most JRPG bosses have tons more HP than a single party member — sometimes more than the entire party combined. Although the order of magnitude is different (JRPG bosses often have thousands of hit points compared to the hundred or so that a strong TTRPG boss might), the reasoning is the same:

More HP = more rounds of combat, which really helps balance out the action economy and prevents D&D parties from just nuking the boss down in one or two rounds.

There’s a sweet spot here, of course — too many hit points and the fight becomes a slog, but particularly when pitting a Dungeons and Dragons BBEG against a larger party, don’t be afraid to add some additional hit points to beef them up.

One of my favorite tricks is to connect “chunks” of this additional HP to a creature’s Legendary Resistance ability. If the party forces the creature to use one of tis Legendary Resistance charges, instead of it just being a “nope, that doesn’t work” moment, the party can remove a large chunk of the boss’s HP.